Good Data could Save Two Million Hectares of Degraded Conservation Areas

Forests are essential for people and the planet, not only because of the contribution of forest products to local welfare but also due to their role as a natural infrastructure to store carbon. Yet every year, massive deforestation and land degradation persist worldwide. Indonesia sees more than 24 million hectares of degraded land, equivalent to almost twice the size of England. Two million hectares of which come from the conservation areas, including national parks, natural reserves, and wildlife reserves. With such large size of degraded land, restoration is inevitable.

Forest and landscape restoration initiatives, including those in conservation areas, will not only revive ecological and biodiversity function, but also bring substantial economic and social benefits. Forest restoration in Latin America, for instance, could potentially bring $1,140 of monetary returns per hectare from wood and non-wood forest products, agricultural production and ecotourism. It is thus instinctive that Indonesia’s Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF), through its 2015-2019 Strategic Plan, sets a target to restore 100,000 hectares of degraded land in conservation areas by 2019 although the achievement remains low.

One key challenge to achieve such a target is the lack of financial resources for restoration activities. With an average annual budget of IDR 15 billion ($1.1 million) between 2015-2017, the government only achieved 55% and 13% of its annual restoration targets in 2015 and 2016 respectively. To fill this funding gap, public-private-people approach for restoration in conservation areas has been pursued by the MoEF.

We analyzed over 90 restoration partnerships in 51 Indonesia’s national parks with data gathered from a public-private-people coordination meeting on restoration in conservation areas organized by MoEF and from Directorate General for Ecosystem and Natural Resources Conservation's 2016 Statistics. In particular, we examined the distribution of restoration partnerships and targets to better understand the existing trends of restoration initiatives in conservation areas. Our findings are outlined below, although they are rather indicative as some data, such as restoration partners' activities and achievements, are not publicly available and hence are not included in the analysis.

Current Restoration Partnerships Are Concentrated in Western Indonesia and They Largely Overlooked Degraded Lands

The interactive map below shows the distribution of restoration partnerships in all national parks in Indonesia.

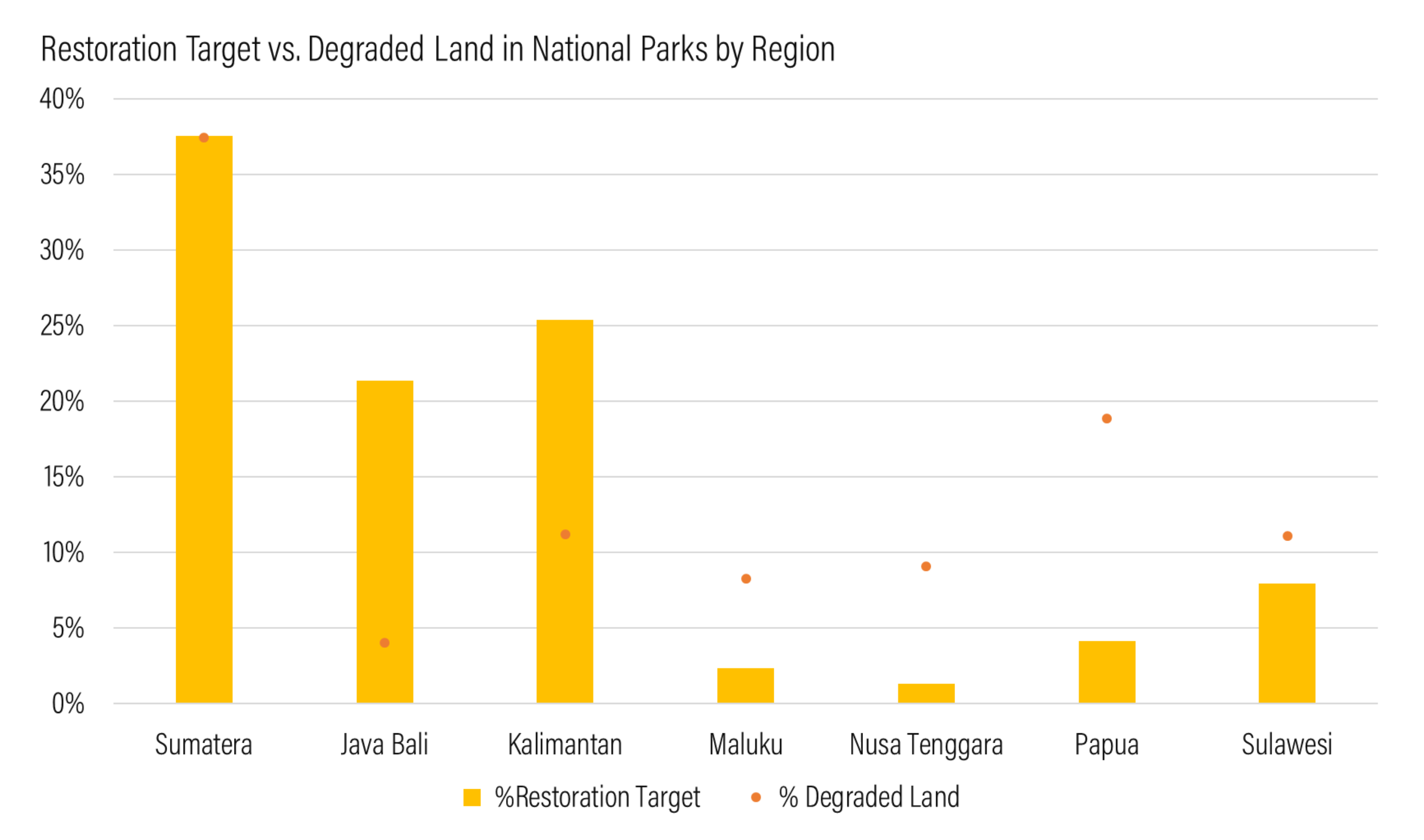

Restoration activities in Indonesia remain concentrated in the western part of the country, including in Sumatera, Java, Bali and Kalimantan. This trend follows the distribution of restoration target laid out in the MoEF’s strategic plan, whereby western Indonesian regions take up 85% of the total target. However, this distribution might not necessarily reflect the needs for restoration.

Based on MoEF’s land degradation classifications (critical and very critical) and 2013 spatial data on land degradation, the extent of degraded land in all national parks in Indonesia nearly reached a million hectare. That said, even if MoEF’s 2015-2019 restoration target is achieved, it will only contribute to recover 10% of the total degraded land in all national parks.

Although the Ministerial Decree No. 18/2016 on Location Designation for Ecological Restoration in Degraded Conservation Areas stated that restoration target should be based on 2013 land degradation data, restoration target set in the Strategic Plan may not be able to address the actual needs. The chart above shows that regions in the eastern part of Indonesia such as Maluku, Nusa Tenggara, Papua and Sulawesi see a huge gap between degraded land and restoration targets, implying a lesser restoration priority in these regions despite their vast degraded lands. In other words, restoration initiatives which are concentrated in western Indonesia could help achieve overall restoration target but it might leave vast degraded lands in eastern part unrestored.

So, what can be done to narrow such a gap?

Better Data for Better Decision Making

In determining the locations of restoration activities, each restoration partner has different decision-making and information processing mechanisms, such as cost-benefit analysis and risk assessment. To assist their decision-making, reliable restoration data, including restoration target, land degradation distribution, target achievement and restoration projects distribution, are crucial. To improve these restoration data, MoEF should ensure that its restoration target is aligned with land degradation distribution as it will set a course for restoration partners to restore areas which receive less attention and make restoration efforts evenly distributed based on the needs. When disseminated effectively, such data could help stakeholders adjust their restoration priorities based on the areas in need.

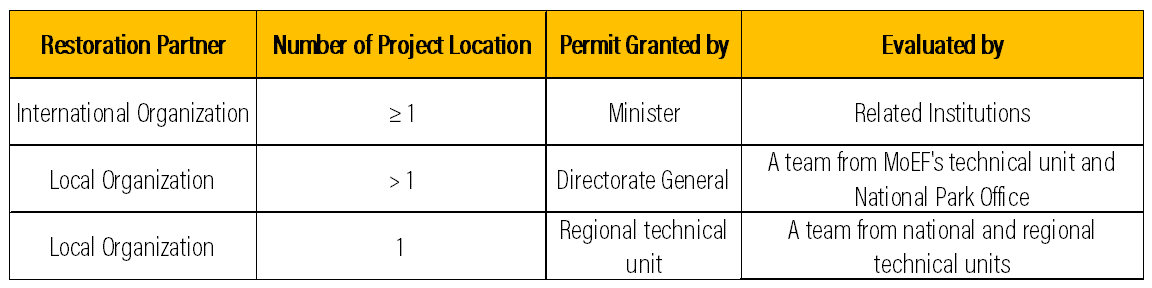

Source: Ministerial Regulation No. 85/2014

As shown in the above table, local organizations who seek to implement restoration projects in only one site are required to secure the permission from relevant regional technical unit, not MoEF. While project reports from these organizations are to be submitted to MoEF, the discussion during the coordination meeting showed that not all restoration projects are reported up to national level. This resulted in incomplete and inconsistent restoration data between national and local administrations.

To address this issue and to ensure a more effective policy-making and planning, a proper reporting mechanism should be put in place. We can start by building a closer coordination between stakeholders, including government and non-government institutions, to provide actual restoration information, including annual and interim reports. This process could strengthen the existing partnership procedure outlined in Ministerial Regulation No. 85/2014. This information will be essential to avoid any pileup of restoration activities in certain areas, monitor the progress of target achievement, and eventually improve restoration data quality.

Upon having reporting mechanism being put in place, MoEF should proactively make the data available to the public. By having restoration-related data disclosed to the public, it will help raise the awareness about restoration needs and assist potential restoration partners in determining their restoration locations and strategies. The partners, including local communities, will be able to see where the needs are, how much progress has been made, and whether further support from the government is needed in restoring degraded lands in conservation areas. Easily accessible data can also serve as a springboard for a more seamless information exchange between all stakeholders. After all, both accurate data and continuous multi-stakeholder dialog are among the key enabling factors for a successful forests and landscape restoration, especially in conservation areas.