3 Key Interventions to Support the Ban on Single-Use Plastic

In an archipelago such as Indonesia, the ocean is not only vital to ecological balance, but also to the lives and livelihood of the people. “Life & Livelihoods” is the theme of this year’s World Oceans Day on 8 June 2021. Unfortunately, Indonesian ocean is still facing many challenges, including marine debris management, which includes plastic debris, a key national agenda.

According to a study on 192 coastal countries in 2010, Indonesia is the world’s second largest contributor of marine debris. Meanwhile, other countries with similar coastal population size, such as India, ranks much further down in the 12th place.

Based on the analysis of Global Plastic Action Partnership, Indonesia’s waste collection capacity is estimated to be at a mere 39 percent, with a recycling capacity of 10 percent. This explains the amount of trash flowing into the ocean due to unmanaged waste on land.

On the other hand, plastic waste in Indonesia is predicted to grow as a result of the development of plastic-intensive sectors and industries, such as the food and beverages industry, which is estimated to grow by 5-7 percent and predicted to continue to grow rapidly.

Marine debris endangers our health. For example, it produces microplastic in our food. The study of Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) shows that 89 percent of anchovies fished in Indonesian ocean are exposed to microplastic, and an average Indonesian consumes up to 1,500 microplastics from fish consumption. Microplastic and plastic chemical have significant effect on the human body, such as human metabolic disorder, as well as ecological and community health risks.

Seeing the great impact of marine debris on our lives, the transformation to reduce plastic use is urgently needed. Many countries and cities in the world have issued policies to reduce their waste and plastic.

The importance of single-use plastic ban

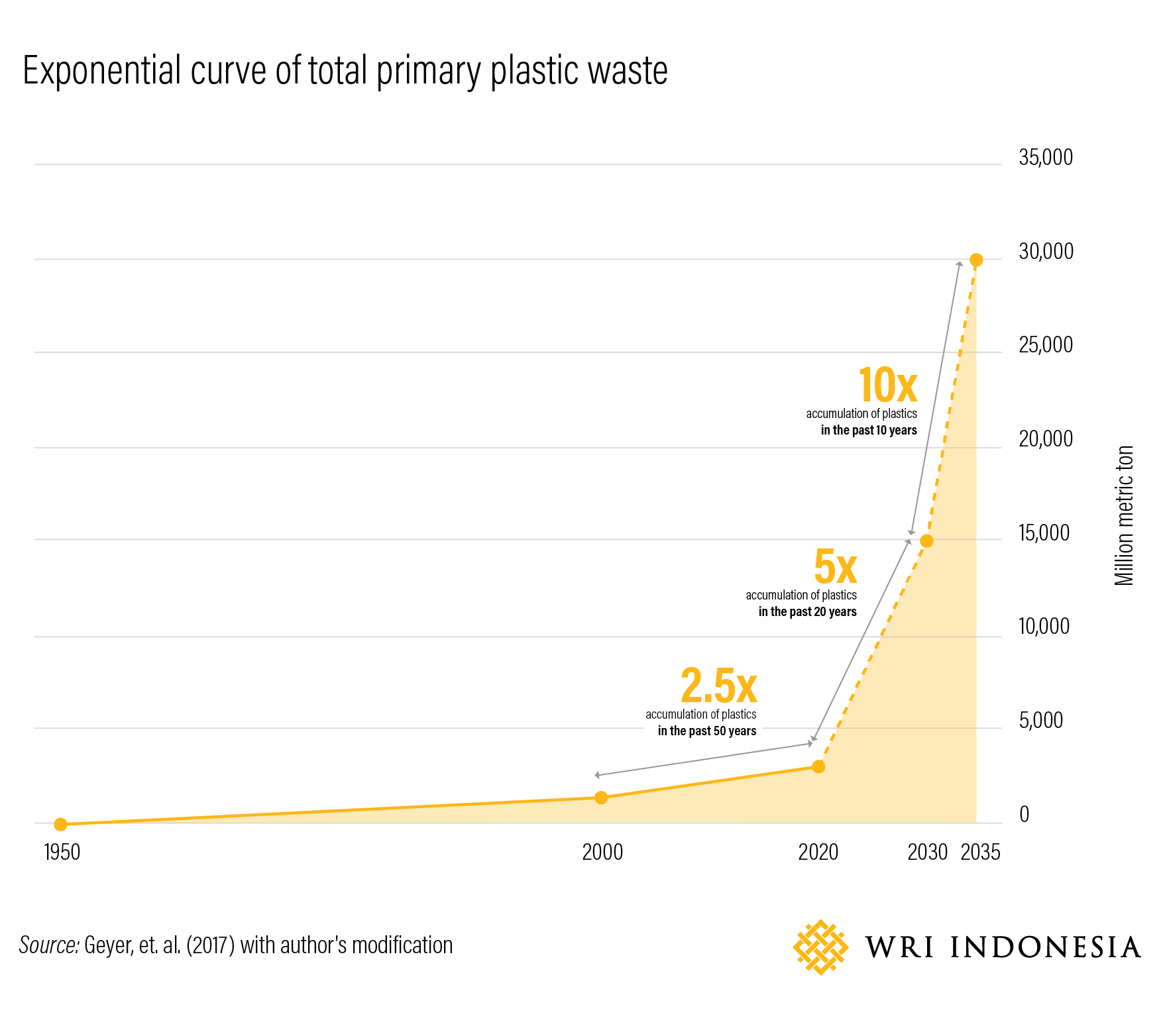

Single-use plastic ban is one of the most commonly used policy instrument to restrict its use. Single-use plastic – plastics that are disposed after one use – leads to exponential growth of plastic waste (instead of linear). This in turn leads to more rapid and faster growth of plastic waste.

In the last 20 years, the amount of plastic in the ocean is the same as the total amount of plastic in the ocean in the previous 50 years. Problematic single-use plastics include shopping bags, food packaging, plastic bottles, plastic sachets and others.

Single-use plastic ban is the manifestation of the waste management hierarchy. It is a waste management method that primarily focuses on avoiding, rethinking and refusing, followed by reusing and recycling. Meanwhile, plastic disposal at a landfill is the last choice to be avoided as much as possible. This approach is a part of the strategy toward zero waste.

As such, a number of Indonesian cities, including Jakarta, have banned the use of single-use plastic. Jakarta took the measure because 34 percent of waste at the Bantar Gebang landfill (TPA) – the disposal site for greater Jakarta – is single-use plastic. Moreover, LIPI’s observation in Jakarta Bay found that 45 percent of waste from Jakarta that ends up in Jakarta Bay is single-use plastic packaging (plastic bottles (7%), plastic cups (9%), plastic covers (4%), thin plastic wrap (7%), thick plastic wrap (6%), straws (6%) and plastic tools (6%)).

A 2018 report of UNEP and World Resources Institute found that at least 127 countries had adopted regulation targeted to govern single-use plastic bags. Canada has banned single-use plastic since 2021 and Peru has banned single-use plastic in 76 natural and cultural protected areas. Moreover, 170 UN countries, including Indonesia, have made commitment to the ‘significant reduction’ of plastic use by 2030, although no clear definition for ‘significant’ has been set.

The Indonesian government has made the commitment to put a national ban on single-use plastic. This started on 1 January 2030 (Regulation of the Minsitry of Environment and Forestry No. 75 of 2019). Banned single-use plastic includes plastic sachets, plastic straws, plastic bags, single-use food containers and utensils. The ministerial regulation is also pushing for recycling prior to the effective date of the ban.

A few researches have documented the plastig bag pollution reduction in each country. In China, the ban on plastic bag has led to a 49-percent decrease in the use of new bags. However, the effect of such ban differs among consumer groups, geographies and shopping objectives. Meanwhile, in the State of California, the United States of America, the ban has led to plastic bag waste reduction of 72 percent by 2017 compared to 2010.

In other countries however, plastic ban has yet to succeed in getting rid of plastic waste. In Bangladesh for example, despite a plastic ban having been in effect since 2002, no significant plastic use reduction has been recorded due to the lack of enforcement. Studies found that in a number of cities in California, the USA, plastic bag ban that is not accompanied by other measures leads to significant increase of paper bag use compared to before the ban.

The question remains, in addition to single-use plastic ban, what is needed in Indonesia to meet the reduction target for single-use plastic by 1 January 2030?

First, push for transformation among manufacturers to use collectable and recyclable packaging as well as reduce the use of single-use plastic. In many cities, the single-use plastic ban, especially plastic bags, mostly focuses on consumer intervention. The same transformation is needed on the manufacturer’s side. The zero waste hierarchy, comprising avoiding, rethinking and refusing, must be adopted by consumers and other key actors, including manufacturers and businesses.

The roadmap for manufacturers serves as guidelines for the private sector for the management, the reuse and the recycling of plastic waste.

An example at the global level is the commitment of fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) companies to reduce plastic use through plastic design innovation, recyclable material content increase and reusable plastic use. A similar commitment is now emerging among plastic manufacturers to using reusable and recyclable plastic. Now we are just waiting to see the practical implementation of such commitment.

Second, developing regulations to support radical efficiency measures for plastic reuse and repurposing. The roadmap for manufacturers is a great first step by the government. However, such roadmap for manufacturers requires more details, such as regulation on recyclable content in plastic and the right take-back system for plastic. Other necessary steps are raising awareness and education on plastic waste reduction.

The government as regulators also needs to anticipate the possible adverse effect of plastic ban and reduction policies, such as workers firing and reduced economic activity. As such, equitable transition that secures environmental conservation, decent jobs as well as social inclusion and poverty eradication is needed. Securing equitable transition will open up opportunities for multi-party collaboration and participation in pushing for such transition.

Third, pushing for single-use plasic reduction innovation on all fronts. Innovation pertains not only to new technology such as new plastic material, but also to business model, policy and economic incentive instrument innovations. An example of this is new household product refilling station businesses that allow consumers to buy products in small amounts in reusable containers, akin to the business models of Siklus and Koinpack. This the type of quick win we need in the effort to reduce plastic waste.